Source: Science Direct

Highlights

Most of the patients with critical COVID-19 admitted to the 10 ICUs in Mexico were men over 57 years of age with hypertension and diabetes, and 6% were health-care workers.•

Patients with hypertension and diabetes had significantly decreased survival, but neither of these comorbidities were an independent factor associated with mortality•

Patients with critical COVID-19 who died in the hospital exhibit significantly higher C-reactive protein concentrations than survivors in our study

Abstract

Background

As of June 15, 2020, a cumulative total of 7,823,289 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported across 216 countries and territories worldwide. However, there is little information on the clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients with severe COVID-19 who were admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) in Latin America. The present study evaluated the clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients with severe COVID-19 who were admitted to ICUs in Mexico.

Methods

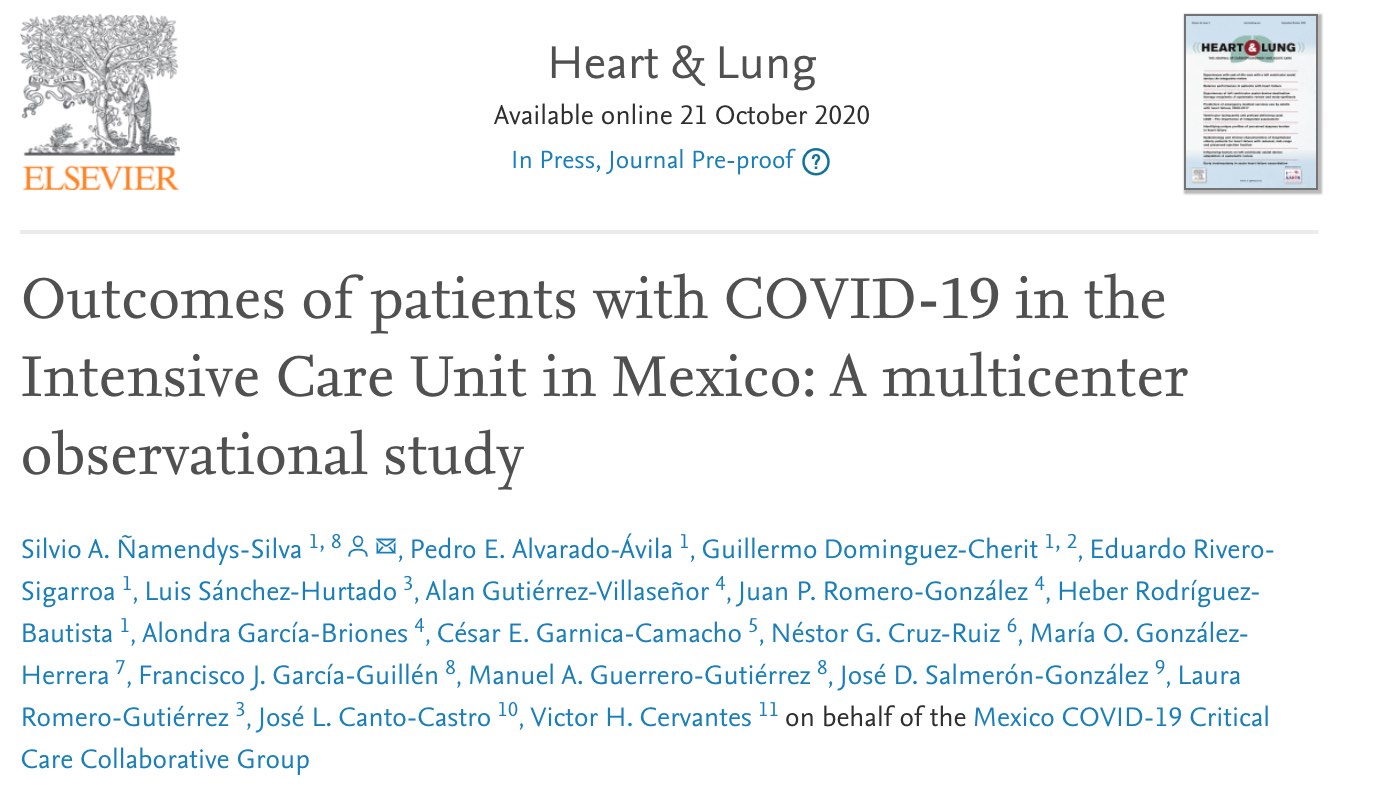

This was a multicenter observational study that included 164 critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 who were admitted to 10 ICUs in Mexico, from April 1 to April 30, 2020. Demographic data, comorbid conditions, clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes were collected and analyzed. The date of final follow-up was June 4, 2020.

Results

A total of 164 patients with severe COVID-19 were included in this study. The mean age of patients was 57.3 years (SD 13.7), 114 (69.5%) were men, and 6.0% were healthcare workers. Comorbid conditions were common in patients with critical COVID-19:38.4% of patients had hypertension and 32.3% had diabetes. Compared to survivors, nonsurvivors were older and more likely to have diabetes, hypertension or other conditions. Patients presented to the hospital a median of 7 days (IQR 4.5-9) after symptom onset. The most common presenting symptoms were shortness of breath, fever, dry cough, and myalgias. One hundred percent of patients received invasive mechanical ventilation for a median time of 11 days (IQR 6-14). A total of 139 of 164 patients (89.4%) received vasopressors, and 24 patients (14.6%) received renal replacement therapy during hospitalization. Eighty-five (51.8%) patients died at or before 30 days, with a median survival of 25 days (Figure 2). Age (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02-1.08; p<0.001) and C-reactive protein levels upon ICU admission (1.008; 95% CI, 1.003-1.012; p<0.001) were associated with a higher risk of in-hospital death. ICU length of stay was associated with reduced in-hospital mortality risk (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84-0.94; p<0.001).

Conclusions

This observational study of critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 who were admitted to the ICU in Mexico demonstrated that age and C-reactive protein level upon ICU admission were associated with in-hospital mortality, and the overall hospital mortality rate was high.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04336345.

Keywords

COVID-19SARS-CoV-2 infectioncoronavirusintensive care unitMexicooutcomes

Introduction

As of June 15, 2020, a cumulative total of 7,823,289 confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been reported across 216 countries and territories worldwide1. A total of 150,262 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 17,580 deaths have been reported in Mexico2. Approximately 3% (4,555/150,262) of these patients presented rapidly progressive respiratory failure and required endotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation2. The COVID-19 pandemic continues to pose a major public health threat to Latin American countries, including Mexico. Although scientific knowledge of COVID-19 increases daily, limited information is available on the presenting characteristics and outcomes of Latin American patients requiring admission to intensive care units (ICUs). Therefore, the present study evaluated the clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients with critical COVID-19 who were admitted to ICUs in Mexico.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study examined 10 hospitals located in Mexico (Appendix). Institutional review board approval was obtained from the participating hospitals in accordance with local ethical regulations. This multicenter observational study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04336345). Each center collected data on all adult patients (age 18 years and older) who were admitted to the ICU between April 1 and April 30, 2020. All patients included in the study had SARS-CoV-2 infection, which was confirmed by positive polymerase chain reaction testing of nasopharyngeal specimens. Patients who died within 24 hours after ICU admission were excluded. The primary outcome parameter was in-hospital mortality (i.e., mortality 30 days following hospital admission).

Data Collection and Definitions

The investigators collected data using preprinted (recorded by each center on an electronic worksheet) or electronic case report forms using a secured internet-based website (EasyTrial COVID-19 server: https://covid19.easytrial.net). Two investigators reviewed the data for plausibility and the availability of primary and secondary outcome measures. Any doubts were clarified with the center in question. There was no on-site monitoring. Data collection upon ICU admission included demographic data and comorbid diseases. Clinical and laboratory data for APACHE II3, SOFA4 and MEXSOFA5 scores were reported as the worst values within 24 hours after ICU admission. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected during the first day of the ICU stay and included the need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), prone position, need for vasopressor therapy, need for renal replacement therapy, length of IMV, length of stay in the hospital before ICU admission, bacterial/fungal coinfection, treatment (renal replacement therapy, vasopressors, antiviral agents, glucocorticoids, tocilizumab, hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin, chloroquine, and any antibiotics), and hospital mortality. Length of ICU stay was measured as the number of days from ICU admission until ICU discharge. The presence of the following comorbid conditions was recorded: systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, solid tumor, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic renal failure. The severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome was defined as mild, moderate or severe according to the Berlin definitions6. Critical COVID-19 patients were defined as patients who required endotracheal intubation at any time during hospitalization or who experienced life-threatening complications, such as ARDS, shock, and/or organ dysfunction7. Clinical laboratory testing was performed in the laboratories of each participating site. Because not all participating centers had the capacity to assess all inflammatory/injury markers, we recorded routine blood test results that were performed as part of the usual clinical care of each patient, which included blood count, serum creatinine, total bilirubin, D-dimer, ferritin and C-reactive protein, where available. We used global reference ranges for the interpretation of laboratory results and the International System of Units to ensure that laboratory values from all local laboratories were converted to the same unit.

Statistical Analysis

No statistical sample size calculation was performed a priori, and sample size was equal to the total number of patients with critical COVID-19 who were treated at participating centers during the study period. All patients completed follow-up examinations by June 04, 2020. Continuous variables are expressed as means (SD) and medians (IQR). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Missing data were not imputed. Student’s t-test (for normally distributed data) or the Mann–Whitney U-test (for nonnormally distributed data) were used to compare continuous variables. Data distributions were determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Chi-squared test (for normally distributed data) and Fisher’s exact test (for nonnormally distributed data) were used to compare categorical variables. Variables with a p<0.05 in the univariate analysis were entered into the model using a forward stepwise procedure. A variable was entered into the model using a forward stepwise procedure (sequentially entering significant variables) if its associated significance level was p<0.05, and a variable was removed from the model if its associated significance level was p>0.100. The age of the patient, C-reactive protein levels on ICU admission and ICU length of stay were entered in the analysis as continuous measures. The remaining variables (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, expectoration, and tocilizumab treatment) were considered categorical factors and were valued as 0 if absent and as 1 if present. The APACHE II scores were not entered into the multivariable analysis due to their possible collinearity with age because age is included in this scoring system. The length of IMV and hospital length of stay were not entered into the multivariable analysis due to possible collinearity with length of ICU stay. The results are summarized as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was used to evaluate the ability of the model to discriminate between patients who lived and patients who died (discrimination)8. Goodness-of-fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow) was calculated to assess the relevance of the logistic regression model9. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The flow chart of this study is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 164 patients with critical COVID-19 were included. Table 1 reports presenting characteristics, treatment in the ICU and outcomes of patients with severe COVID-19, according to in-hospital death. Mean age was 57.3 years (SD 13.7), and 114 patients (69.5%) were men. The mean body mass index was 30.7 kg/m2, and 10 patients (6.0%) were healthcare workers. A total of 38.4% of patients had hypertension, and 32.3% had diabetes (Table 1). Demographic variables and comorbidities were compared between survivors and nonsurvivors. Nonsurvivors were older and more likely to have comorbid conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. Patients presented to the hospital a median of 7 days (IQR 4.5-9) after symptom onset. The most common presenting symptoms were shortness of breath, fever, dry cough, and myalgias. A total of 164 (100%) patients received IMV for a median of 11 days (IQR 6-14), 139 (89.4%) patients received vasopressors, and 24 (14.6%) received renal replacement therapy during hospitalization. Seven (4.2%) patients received high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy or noninvasive ventilation, and 100% of patients subsequently required IMV. Laboratory findings of critically ill patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 on admission to the ICU are presented in Table 2. Infections were microbiologically confirmed in 26 (15.9%) of 164 patients. Antibiotics were administered empirically to 162 of 164 (98.7%) patients. Antiviral agents were also administered to 86 (52.4%) patients in this study (Table 1). The median length of ICU stay among survivors was 13 days (IQR 10 to 16), and the median length of hospital stay among survivors was 15 days (IQR 12 to 19) (Table 1). Eighty-five (51.8%) patients died at or before 30 days, with a median survival of 25 days (Figure 2). Age (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02-1.08, p<0.001) and C-reactive protein levels upon ICU admission (OR, 1.008; 95% CI, 1.003-1.012, p<0.001) were associated with an increased risk for in-hospital death. ICU length of stay was associated with reduced in-hospital mortality risk (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84-0.94, p<0.001) [goodness of fit, (Hosmer-Lemeshow), χ2=4.806, p=0.778, AUC: 0.79 (95% confidence interval: 0.73-0.86), p<0.001] (Table 3).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study and included patients with critical COVID-2019.

Table 1. Characteristics, treatment in the intensive care unit and outcomes of patients with critical COVID-19 based on in-hospital death.

| Characteristic | All Patients (n=164) | Alive (n=79) | Dead (n=85) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 57.3 ± 13.7 | 49.4 ± 13.1 | 57.0 ± 13.3 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 114 (69.5) | 55 (69.6) | 59 (69.4) | 0.977 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 mean ± SD | 30.7 ± 5.5 | 30.2 ± 4.9 | 31.2 ± 6.0 | 0.272 |

| APACHE II, mean ± SD | 12.7 ± 5.5 | 11.8 ± 5.0 | 13.6 ± 5.9 | 0.039 |

| SOFA score, median (IQR) | 6 (4-8) | 6 (4-8) | 6 (4-8) | 0.676 |

| MEXSOFA score, mean ±SD | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 5.8 ± 2.4 | 6.1 ± 2.1 | 0.440 |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Systemic hypertension | 63 (38.4) | 22 (27.8) | 41 (48.2) | 0.010 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 53 (32.3) | 16 (20.2) | 37 (69.8) | 0.001 |

| Smoking | 24 (14.3) | 13 (16.4) | 11 (12.9) | 0.659 |

| Solid tumors | 10 (6.0) | 6 (8.6) | 4 (4.7) | 0.524 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 (2.4) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.5) | 0.621 |

| Chronic renal failure | 6 (3.6) | 4 (5) | 2 (2.3) | 0.430 |

| Signs and symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Shortness of breath | 152 (92.6) | 70 (88.6) | 82 (96.4) | 0.053 |

| Fever | 138 (84.1) | 67 (84.8) | 71 (83.5) | 0.822 |

| Dry cough | 131 (79.8) | 60 (75.9) | 71 (83.5) | 0.226 |

| Myalgia | 84 (51.2) | 44 (55.6) | 40 (47.0) | 0.269 |

| Expectoration | 32 (19.5) | 9 (11.3) | 23 (27.0) | 0.011 |

| Rhinorrhea | 31 (18.9) | 15 (18.9) | 16 (18.8) | 0.979 |

| Diarrhea | 29 (17.6) | 10 (12.6) | 19 (22.3) | 0.104 |

| Duration of symptoms before hospital admission, days, median (IQR) | 7 (4.5-9) | 7 (4-9) | 7 (5-9) | 0.526 |

| ARDS mild to moderate, n (%) | 93 (56.7) | 48 (60.7) | 45 (52.9) | 0.313 |

| ARDS severe, n (%) | 71 (43.3) | 31 (39.2) | 40 (47.1) | |

| Treatment, n (%) | ||||

| High flow nasal cannula | 5 (3.0) | 4 (5.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.197 |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0.271 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 164 (100) | 79 (100) | 85 (100) | NA |

| Prone position | 93 (56.7) | 43 (54.4) | 50 (58.8) | 0.570 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 24 (14.6) | 11 (13.9) | 13 (15.3) | 0.804 |

| Vasopressors | 139 (89.4) | 69 (87.3) | 70 (82.3) | 0.374 |

| Antiviral agents | 86 (52.4) | 38 (48.1) | 48 (56.4) | 0.284 |

| Glucocorticoids | 66 (40.2) | 27 (34.1) | 39 (45.8) | 0.127 |

| Tocilizumab | 42 (25.6) | 28 (35.4) | 14 (16.4) | 0.005 |

| Hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin | 54 (32.9) | 30 (37.9) | 24 (28.2) | 0.185 |

| Chloroquine | 48 (28.0) | 27 (34.1) | 19 (22.3) | 0.092 |

| Any antibiotics | 162 (98.7) | 79 (100) | 83 (97.6) | 0.498 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation, days, median (IQR) | 11 (6-14) | 12 (7.5-15) | 8 (5-13) | 0.003 |

| ICU length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 12 (7-15) | 13 (10-16) | 8 (5-13) | <0.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 13 (8-18) | 15 (12-19) | 10 (7-14) | <0.001 |

SD: standard deviation; APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, MEXSOFA: Mexican Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; IQR: interquartile range, ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU: intensive care unit

Table 2. Laboratory findings on intensive care unit admission of patients with critical COVID-19 based on in-hospital death.

| Laboratory values | All Patients (n=164) | Alive (n=79) | Dead (n=85) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, mean ± SD | 13.5 ± 2.17 | 13.3 ± 2.1 | 13.7 ± 2.2 | 0.251 |

| White blood cells count, 109/L, median (IQR) | 10.5 (7.4-13.0) | 11 (8.1-12.8) | 10 (7.3-13.5) | 0.407 |

| Neutrophils, 109/L, mean ± SD | 9.1 ± 4.9 | 9.3 ± 5.1 | 8.9 ± 4.8 | 0.626 |

| Lymphocytes, 109/L, median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.5-1.1) | 0.8 (0.5-1.1) | 0.8 (0.5-1.1) | 0.880 |

| Platelets, 109/L, mean ± SD | 252 ± 95.3 | 246 ± 101 | 259 ± 89.4 | 0.374 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 1.05 (0.81-1.56) | 1.16 (0.81-1.72) | 0.95 (0.76-1.39) | 0.172 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 0.65 (0.42-0.88) | 0.61 (0.40-0.81) | 0.69 (0.49-0.98) | 0.089 |

| D-dimer, μg/ml, median (IQR) | 1.15 (0.68-2.53) | 1.16 (0.73-2.84) | 1.16 (0.68-2.1) | 0.420 |

| Ferritin level, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 944 (565-1375) | 888 (520-1119) | 997 (620-1531) | 0.054 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 31 (17.9-131.4) | 25 (12.7-32) | 54 (27.8-213) | <0.001 |

SD: standard deviation, IQR: interquartile range

Figure 2. Survival of critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Table 3. Variables predictive of in-hospital mortality according to univariate and multivariate analyses.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |||

| Age | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 0.001 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.08 | <0.001 |

| Systemic hypertension | 2.41 | 1.26 | 4.62 | 0.008 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.03 | 1.51 | 6.09 | 0.002 | ||||

| Expectoration | 2.88 | 1.24 | 6.70 | 0.014 | ||||

| Tocilizumab treatment | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.74 | 0.006 | ||||

| Length of intensive care unit stay | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.95 | <0.001 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.94 | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.008 | 1.004 | 1.01 | <0.001 | 1.008 | 1.003 | 1.01 | <0.001 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first report of patients with critical COVID-19 from Latin America. Most patients with critical COVID-19 admitted to the 10 ICUs in Mexico were men over 57 years of age with hypertension and diabetes, and 6% were health-care workers. As mentioned in previous studies, greater than 60% of patients with critical COVID-18 were men10,11. The mean age of patients admitted to the ICU was 57 years old, which is less than the median age reported in other studies.10,13 Patients with hypertension and diabetes exhibited significantly decreased survival, but neither of these comorbidities was an independent factor associated with mortality. One hundred percent of patients received IMV, and nearly 90% received vasopressors. Compared to other reports,10, 11,12 this study corroborates the very high incidence of multiple organ failure in patients with severe COVID-19, as shown by the proportion of patients requiring IMV (164 [100%]), vasopressors (139 [89.4%]) and renal replacement therapy (24 [14.6%]).

C-reactive protein is an acute inflammatory factor that increases up to 1,000-fold at sites of infection or inflammation.14 Elevated levels of C-reactive protein may be linked to the overproduction of inflammatory cytokines in patients with critical COVID‐19.15 Higher levels of C-reactive protein might be a predictive marker in determining which patients with mild COVID-19 will progress to critical disease.16 Patients with critical COVID-19 who died in the hospital exhibited significantly higher C-reactive protein concentrations than survivors in our study. This result suggests that the C-reactive protein levels upon admission to the ICU may be useful for predicting the prognosis of patients with critical COVID-19. Previous studies reported mortality rates that ranged from 35.2% to 72% in these patients10,12,13,17. In a cohort of 52 critically ill patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection from a single center in Wuhan, China, 32 (61.5%) patients died at 28 days.17 A total of 405 (26%) of 1581 patients and 784 (35.4%) of 2215 patients who were critically ill with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 also died at 28 days in a cohort from Lombardy Region, Italy10 and a US cohort13, respectively. The mortality in our report was higher than that reported in critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Italy10 but lower than in other studies.18,19 Our data confirm high hospital mortality rates in patients with critical COVID-19.

The present study has several limitations. First, the small sample size may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, the retrospective nature of the study is a limitation. Finally, we had no specific information on long-term outcomes or quality of life in survivors. Further research is needed to extend our results in larger cohorts.

Conclusions

The present observational study of critically ill patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 admitted to ICUs in Mexico demonstrated that age and CRP levels upon ICU admission were associated with in-hospital mortality, and the associated hospital mortality rate was high.

Related: