Source: Rounding the Earth Author: Mathew Crawford

The story of why hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has not been used broadly in most Western nations (primarily in the sphere of influence of those countries with the largest pharmaceutical industries) to treat COVID-19 patients during the first days of the disease progression is a bizarre tale.

It involves the strange insistence of the fabrication that RCTs are the only good evidence (history notwithstanding), that late treatment (after viral replication has already shut down) fairly tests antivirals, and what appears to be an organized conspiracy of media silence. But we have only begun to examine the strange details of this story!

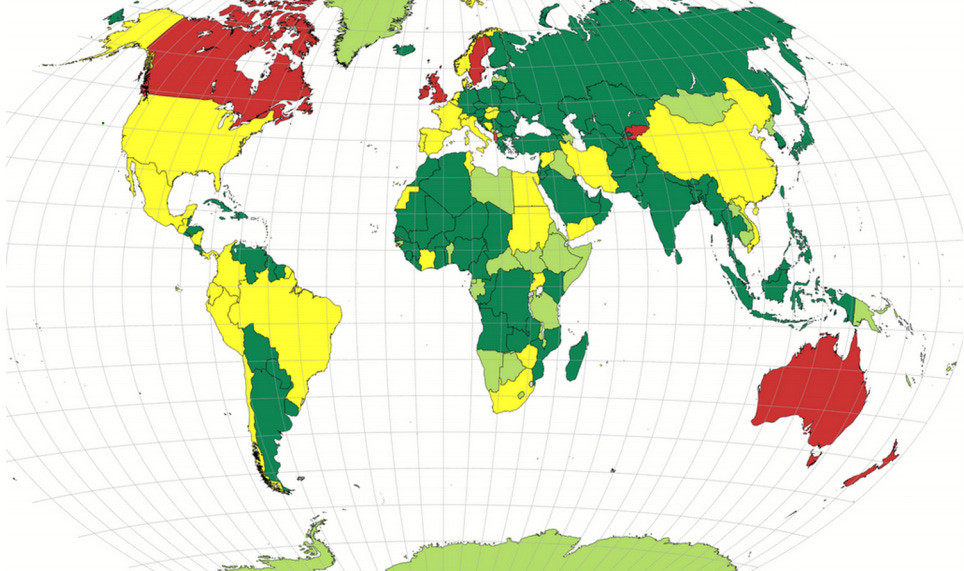

Green = HCQ/CQ allowed liberallyYellow = Mixed allowance or policy change during pandemicRed = Little or now allowance of HCQ/CQ usageLight Green = No policy information that I found (through early November), though no evidence of restrictions either (often OTC)In late 2004, in the wake of the SARS-CoV outbreak that claimed over 8,000 lives across nearly 30 nations, Belgian researcher Els Keyaerts and her team published a paper in the journal Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications entitled “In vitro Inhibition of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus by Chloroquine”.

Keyaerts and her cohorts tested the antiviral properties of chloroquine phosphate on a line of kidney cells extracted from an African green monkey. Using amounts of CQ similar to those used to treat malaria patients, the researchers noted successful antiviral effects (killing of the virus) and cytostatic effects (inhibition of viral replication).

The researchers concluded, “Chloroquine, an old antimalarial drug, may be considered for immediate use in the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV infections.”

Keyaerts’s paper was not the first to explore the effects of CQ and other quinolines on viruses. For decades, scientists have found CQ to be effective in vitro, in vivo, or in humans against flaviviruses such as dengue virus, retroviruses such as HIV, myxovirus, Zika virus, and picornaviruses such as poliovirus. And it does this while working against cell damage caused by some viruses. Less than a year after Keyaerts et al published, an American research team led by Martin J. Vincent published a study in Virology Journal titled “Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread,” reporting in vitro viral inhibition both as prophylaxis and treatment. From that research:

In addition to the well-known functions of chloroquine such as elevations of endosomal pH, the drug appears to interfere with terminal glycosylation of the cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. This may negatively influence the virus-receptor binding and abrogate the infection, with further ramifications by the elevation of vesicular pH, resulting in the inhibition of infection and spread of SARS CoV at clinically admissible concentrations.

This interference with the ACE2 receptor adds to the rationale for testing HCQ efficacy on those infected with SARS-CoV-2, and COVID-19 patients.

This level of versatility of HCQ is quite unusual among drugs. Few drugs are successfully repurposed, so we might wonder: What is it about HCQ that makes it so useful? While nobody knows that answer completely, at least some of HCQ’s medicinal potential stems from a wide array of effects.

First, for reasons researchers do not fully understand, HCQ and CQ block the parasites that cause most malaria from entering the blood stream via the CD147 pathway, which is noteworthy because CD147 is one of the cellular pathways through which SARS-CoV-2 passes (into the bloodstream where it can cause the debilitating microthrombotic effects associated with COVID-19).

Neeraj Sinha and Galit Balayla summarize a broad array of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of HCQ and CQ, relating them generally to viral infections:

The effect of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine on the immune system has been well established. Several of their anti-inflammatory mechanisms have been recognised, for example, interference with lysosomal acidification and antigen presentation,11 inhibition of phospholipase A2,12 absorption and blocking UV light cutaneous reactions,13 binding and stabilising DNA,14 inhibition of toll-like receptor signals, inhibition of T and B cell receptors, and especially, decreasing cytokine production by macrophages such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6.7 11

Interaction with toll-like receptors and T-cell receptors makes hydroxychloroquine effective in different sites of the signalling cascade in the inflammatory response. These interactions prevent autoimmunity without immunosuppressing the patient.15

Sperber et al also demonstrated the inhibition of IL-1 and IL-6 in T-cells and monocytes11 and several other studies have demonstrated tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibition or attenuated inflammatory effect by hydroxychloroquine.16–18

The effective inhibition of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1 and TNF-alpha decreases tissue damage and endothelial inflammation thus preventing initiation and propagation of autoimmune inflammation.19

This cytokine inhibition is of great importance at this time, since it has been demonstrated that several viruses upregulate the expression of IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-alpha in vitro, suggesting the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in viral infections.

CQ also demonstrates activity as a zinc ionophore, enhancing uptake of zinc into cells. While zinc’s general effect on viral immunity is debated in medical literature (zinc has often shown antiviral effects), a 2010 study showed zinc’s in vitro success in blocking replication of coronaviruses. Multiple studies (here and here, diagram below from latter) during the pandemic link zinc deficiency to COVID-19 incidence, severity, and mortality.

In 2007, a team of French infectious disease experts experienced with these medications reviewed the literature, noting the rise of coronavirus epidemics, and predicted that HCQ and CQ would prove even more widely applicable to new diseases through the twenty-first century.

It is clear that for many years, scientists focused on HCQ as a drug with potential to shut down the next coronavirus outbreak. Many rationale papers and opinion pieces were published in medical journals, and a few even in blogs, both years before the pandemic and during its early months.

At the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, hundreds of researchers quickly began registering trials to study the effects of HCQ or CQ both in the U.S. and around the world. In fact, through April 27, 2020, 46 of the 68 repurposed medicine clinical trials registered for prophylaxis (68%) proposed testing HCQ out of all possible options!

Clearly, HCQ was broadly considered the obvious first candidate among researchers as a drug to treat the next coronavirus epidemic (even if our media didn’t want to speak a word about it).

There was one single rationale paper for repurposing medicine published during the early going of the pandemic that did not include any discussion at all of hydroxychloroquine, despite its being the obvious first choice. That’s the one that has NIAID Director Dr. Anthony Fauci’s name on it.

Maybe he had some reason previously unexpressed (and never since) as to why HCQ, which seemed to work so well on SARS-CoV, was not even worth a mention as a potential treatment for SARS-CoV-2? That seems hard to believe without any trial results anywhere in the world prior to the repurposed medicine rationale paper he coauthored—particularly since Fauci’s NIH supported the aforementioned Vincent research in 2005.

So, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the NIAID Director assigned essentially no resources or attention to the potential for HCQ to help those infected with the novel coronavirus. Not even a few dollars to pay for somebody to collect the data from the scores of nations using the treatment.

He even actively dismissed such data as it was being aggregated and collected by others. Instead, nearly all time, attention, and money at the NIAID was focused on rapid production of vaccines (81%), including (at least in the U.S.) nonstandard vaccines never before used on a scale beyond a few hundred participants.

Why was HCQ left off Fauci’s list? I cannot say for certain, but I can think of a few billion reasons.

Related: Journal of Medicine Says HCQ + Zinc Reduces COVID Deaths

The Chloroquine Wars Part V – A Closer Look at RCTs Studying Hydroxychloroquine Efficacy

The Chloroquine Wars Part VI – The Simple Logic of the Hydroxychloroquine Hypothesis

The Chloroquine Wars Part VIII – Hydroxychloroquine’s Safety Profile and a Cost-Benefit Analysis

The Chloroquine Wars Part X – A Discussion of the Insanity of the Chloroquine Wars

The Chloroquine Wars Part XI – See No Good, Hear No Good, Speak No Good

The Chloroquine Wars Part XII – Manufactured Fear During Hydroxychloroquine’s Trump Moment