Source: Rounding the Earth Author: Mathew Crawford

“Hydroxychloroquine alone has a relative effectiveness. Only the combination of the two drugs [HCQ along with azithromycin] is really effective, the value of this treatment is that it is prescribed as soon as possible, before the onset of pneumonia; its effectiveness in severe condition is limited. “

–Dr. Didier Raoult

The primary question: Is hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) effective in fighting SARS-CoV-2 and the associated COVID-19 condition?

This seemingly simple question has resulted in strangely bitter debate, not to mention a great deal of confusion. We do our best to provide a well-reasoned answer, starting with simple logic.

What would it take to answer such a question in either the affirmative or the negative?

First, let us note that it takes far less evidence to answer in the affirmative. The reason for this is that a medication—any medication—can be used in multiple ways.

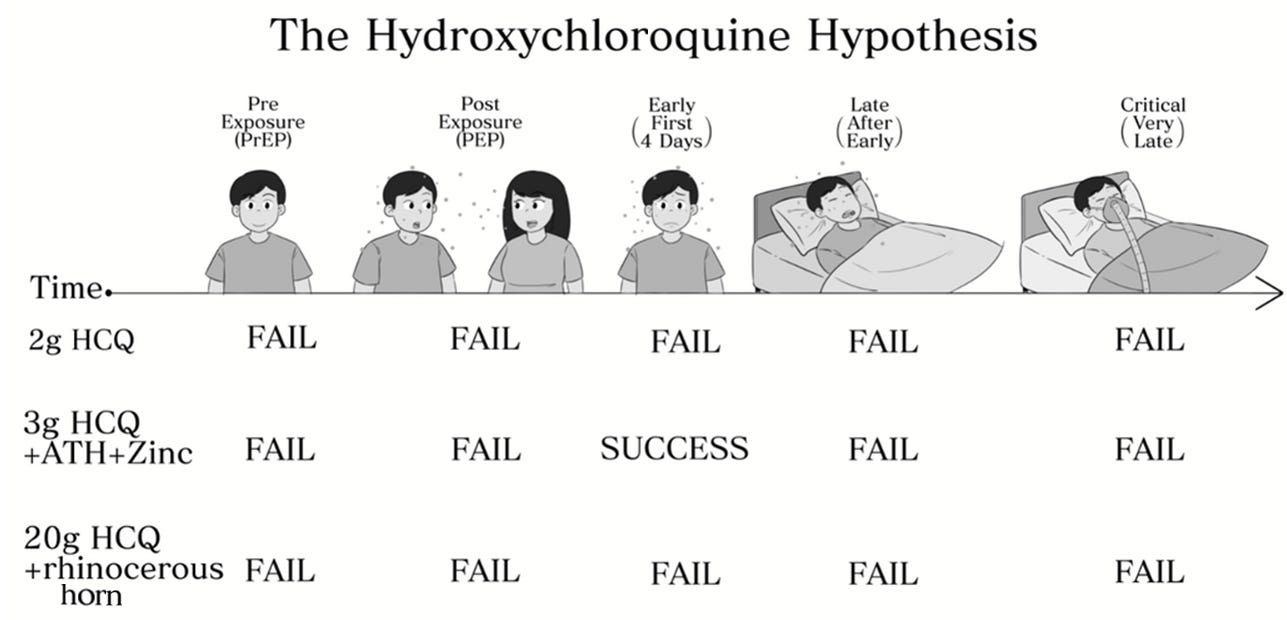

In particular, HCQ has been tested as a pre-exposure prophylactic (PrEP) in healthy individuals, as a post-exposure prophylactic (PEP) in exposed individuals (who may or may not have ingested a viral load sufficient to reach threshold for infection), as an early treatment for patients beginning to exhibit symptoms, as a later treatment for patients whose symptoms have progressed, and also for critically ill patients.

If HCQ proves to be effective in just one of these circumstances, at any dosage, and in any combination with other therapies, then we answer the primary question in the affirmative.

However, in order to answer the primary question in the negative, we must demonstrate that HCQ fails to confer benefit as PrEP, as PEP, for patients in the early symptom stage, late-stage patients with well developed COVID-19, and also for those who are critically ill. This may be the case, but answering the primary question in the negative requires substantial evidence in every one of these circumstances.

Not only that, but we must be certain that the evidence indicates a lack of efficacy of the best possible treatment during each of those circumstances, meaning optimal dosage and as part of an optimal cocktail of medicines and other treatment.

While one, well-run, large experiment may answer the primary question in the affirmative, many studies would be required to answer the primary question in the negative.

The Hydroxychloroquine Hypothesis: That there is some appropriate dosage of hydroxychloroquine, alone or in some combination with other medication, that successfully prevents some COVID-19 cases (PrEP/PEP) or treats some COVID-19 sufferers (Early/Late/Critical).

Thus, logically, the following experimental results would indicate an affirmative answer to the HCQ Hypothesis:

Let us also define a Primary HCQ Hypothesis, which excludes late stage or critical patients. In general, an antiviral treatment should be applied within the first few days of symptoms.

After the symptomatic period, many viruses (including coronaviruses) have been fought off and cleared from the body. At that point, only the symptomatic response or disease state remains. Should the HCQ Hypothesis prove valid, it is almost certainly the case that this is due to evidence affirming the Primary HCQ Hypothesis.

Now, note that the case for the Primary HCQ Hypothesis looks extremely strong:

Out of 29 studies, including half a dozen RCTs, the worst that can be said of any single result is that the study was, on its own, underpowered to achieve statistical significance. However, together, as we clearly see, the aggregated effects meta-study goes far beyond statistical significance. These collective results (or those more positive) would only happen by chance about once in ten random million simulations.

So, how then could it be that so many people still argue that HCQ “proved ineffective”, or as USA Today confidently stated on March 21, 2020, just two days after Trump first mentioned HCQ, “snake oil and false hope” (strangely prior to the publication of much evidence at all, aside from the small pilot Gautret/Raoult et al paper that showed great promise, and the numerous highly positive rationale papers)?

Clearly such declarations defy basic logic as there is no evidence to date that HCQ fails as an early treatment therapy.

Oddly, many scientists and doctors point to WHO trials (which were problematic on many levels: late-stage, using a uniquely high dosage, and without a macrolide or zinc) and the Brazilian study published in the NEJM (because PRESTIGE!), which similarly tested late-stage patients (12% were even recruited from the ICU ward) and in which nearly 40% of the patients in the control group were previously treated with one of the medications being tested (oopsie?).

Even if the aforementioned late-stage experiments were impeccably run and HCQ failed to help late-stage sufferers of COVID-19, they cannot speak to the Primary HCQ Hypothesis—that HCQ effectively treats COVID-19 patients during the early stages.

Remaining entirely unblemished after a year of trials and observations, the current evidence in favor of the Primary HCQ Hypothesis fully validates the HCQ Hypothesis. The logic is so simple that it almost feels like your livelihood would have to be on the line to deny it.

Related: Journal of Medicine Says HCQ + Zinc Reduces COVID Deaths

The Chloroquine Wars Part V – A Closer Look at RCTs Studying Hydroxychloroquine Efficacy

The Chloroquine Wars Part VIII – Hydroxychloroquine’s Safety Profile and a Cost-Benefit Analysis

The Chloroquine Wars Part X – A Discussion of the Insanity of the Chloroquine Wars

The Chloroquine Wars Part XI – See No Good, Hear No Good, Speak No Good

The Chloroquine Wars Part XII – Manufactured Fear During Hydroxychloroquine’s Trump Moment