TUBS, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: Rounding the Earth Author: Mathew Crawford

“One worm may damage the whole cooking soup.” -Vietnamese Proverb

Sharing a border with China, the ostensible source of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, Vietnam was the ninth nation to announce a confirmed infection on January 24, 2020.

Unlike any of the nations that saw an outbreak before them, Vietnam managed to escape the impact of COVID-19, recording barely 500 cases and no deaths until July 31, 2020. As early as February 20, Vietnamese medical officials announced the “development of an effective treatment”.

While stating that the treatment did not depend on a single medicine that could cure patients alone, Vietnamese pharmacies were swamped with purchases in March and the Ministry of Health soon began the process of registering a trial for chloroquine (CQ), which China also selected as its drug of choice for COVID-19 patients on February 19.

It is unclear to me the exact date on which Vietnam stopped using CQ, though this article on August 4 relays the decision:

The information was announced by Nguyen Van Kinh, former Director of the National Hospital for Tropical Diseases and chairman of Vietnamese Society of Infectious Disease, as he discussed the latest revision of the health ministry’s COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment guidelines (the fourth comprehensive update since the coronavirus cases were first recorded in Vietnam in late January).

The health ministry noted that while there had not been a definitive drug to treat COVID-19, a variety of antiviral drugs – including the domestically available lopinavir, ritonavir and interferon – might deliver some results as many patients were cleared of the virus within a week.

Vietnam outlasted Uganda’s perfect record by a week, reporting its first death from COVID-19 on July 31, 2020, coincidentally the same day it was reported that they received millions of dollars from the World Bank to help “cope with COVID-19”. From that moment, Vietnam’s case fatality rate climbed from 0% to around 20%. It is noteworthy that for some reason Our World in Data does not allow users to view the CFR graphs prior to September 1, 2020, even though the data that would be used to do it is available.

Fortunately, the death toll ended in early September in Vietnam, though cases trickled in by a few dozen per week for a few months.

Vietnam’s COVID-19 Vaccine Campaign

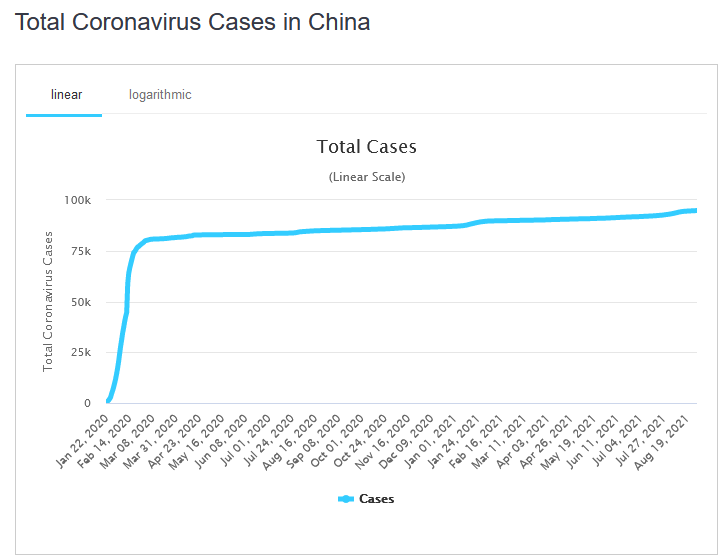

Vietnam began its vaccination campaign on March 8, 2021 after not having suffered a COVID-19 fatality in over six months. Starting with the AstraZeneca vaccine, Vietnam quickly approved Russia’s Sputnik V for use starting 15 days later. For more than two months into the vaccination campaign, Vietnam still reported no new COVID-19 fatalities. Then the situation began to change—slowly at first, and only recently looking to begin to peak at over 200,000 active cases. In the nation that had recorded just 35 COVID-19 deaths prior to May 15, 2021, the death toll currently stands at over 10,000 and will likely head toward 20,000 by the end of September, assuming the situation doesn’t worsen.

Few Vietnamese were vaccinated during the early part of the campaign. Though Chinese vaccines were added to the list of options, anti-Chinese sentiment is reported to have led some Vietnamese to wait for the availability of other brands. U.S. vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna, and then Johnson & Johnson were approved on June 12, June 29, and July 15, respectively, with millions of doses shipped to Vietnam. By late July, Vietnam’s SARS-CoV-2 infection rate soared like never before.

By the end of May, it was reported in news outlets that a new SARS-CoV-2 variant had emerged in Vietnam. We can add that to the essentially complete list of variants of interest that emerged after the introduction of vaccines to a population. A study published in The Lancet (Chau and Ngoc, 2021) on August 10, 2021 notes the association of the emergent variant with breakthrough cases involving “low-levels of vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies” among health care workers who may very well have precipitated the ongoing epidemic.

The Curious View From the West

Looking back at Vietnam’s relative success with COVID-19 during 2020, consider stories like this one told by the Western media. There is not a single mention of CQ, though the author talks about Vietnam’s younger population, then waxes poetically about the success of localized and targeted public health surveillance. However, while variables like CQ and vaccines changed, and we can judge the results as natural experiments, there is no evidence that the case trackers stopped trying to do their jobs. CNBC suggests that Vietnam “punched above its weight” using large-scale quarantines and closing borders. Somehow, those tactics don’t seem to be holding up now.

Why do Asian countries use hydroxychloroquine for Covid-19 despite Western rejection?

Uganda’s Tale of COVID-19, Medicine, and Vaccination: Pandemic National Case Studies

Demand Early Treatment! – All questions Covid with Dr. Al Johnson and Dr. Peter McCullough